|

Photo of the Week

December 9, 2017

THIS WEEK'S PHOTOS MAKE 1,000 WEEKS OF THE WEEKLY PHOTOS SINCE I STARTED THIS WEBSITE.

|

|

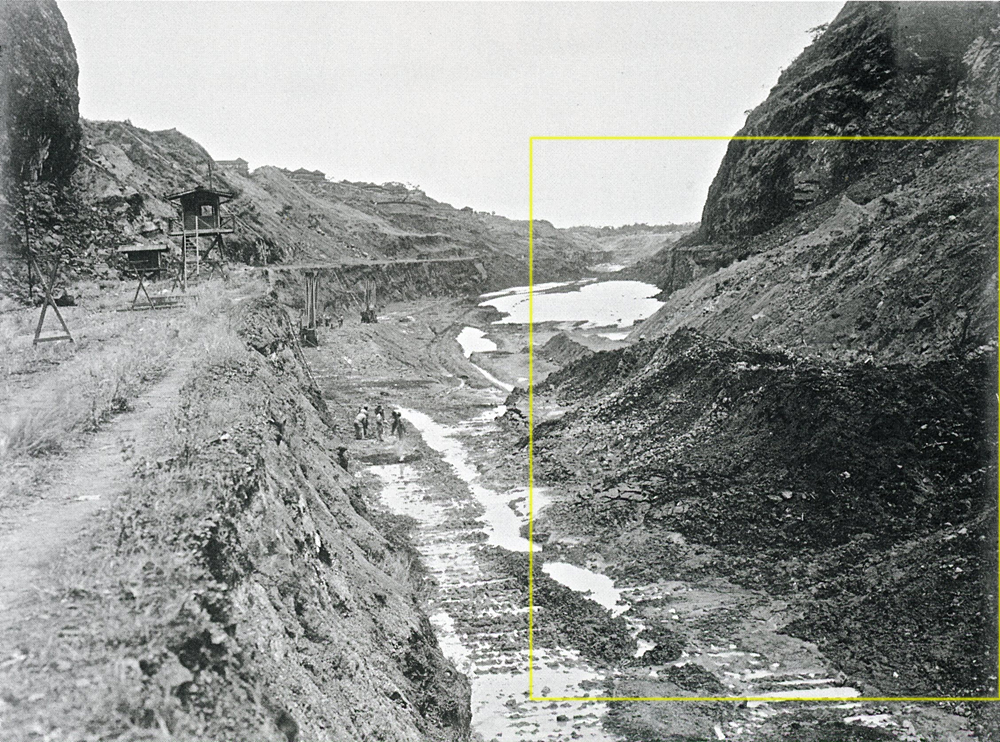

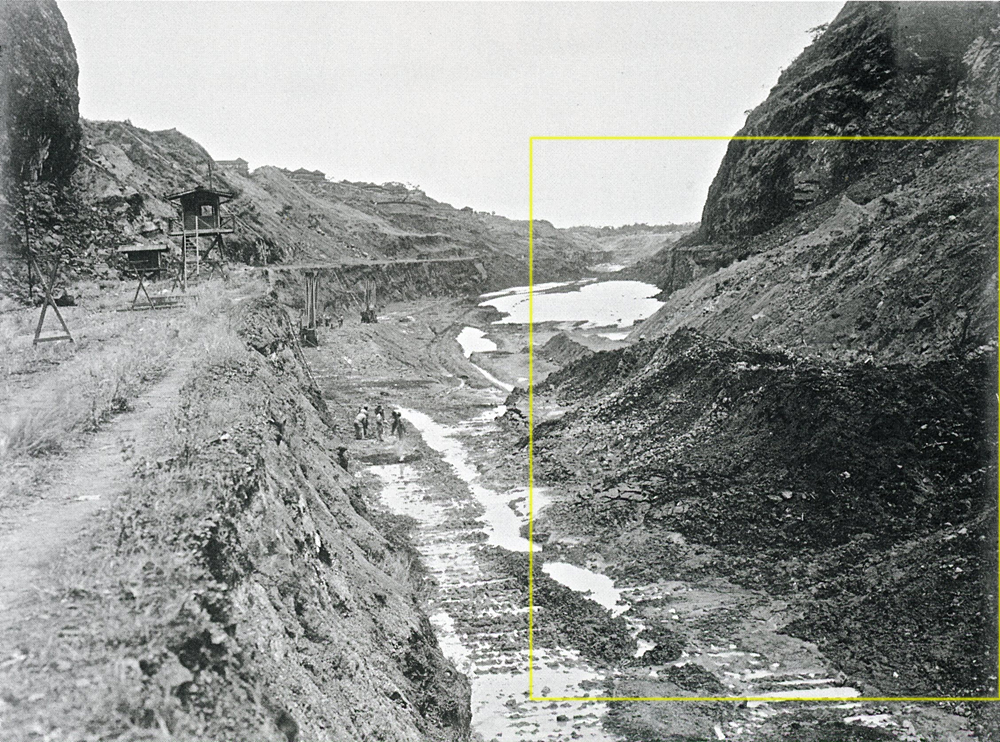

"By the end of the first week of September, 1913, the Canal excavation was essentially finished. All the railroad tracks and steam shovels have been removed in anticipation of flooding the entire Culebra Cut to Pedro Miguel Locks by opening the valves on the dike at Gamboa on October 1, 1913. From now on, the material will have to be dredged. Almost immediately, tremendous slides closed the channel. In the background, just beyond the larger pond, a slide from the west by Culebra and slide from the east, off the north side of Gold Hill, have met in the middle of the channel, effectively blocking it. The only way to remove the material from the slides would be to wait until the dredges could be floated into the area. In the meantime, rains started filling in the area between the slides at the north and south ends of Gold Hill. Many of the dredges were in the Pacific, and sufficient water to float them from Pedro Miguel Locks to the slides would have to come from Gatun Lake once the Culebra Cut was flooded. To fill the channel to Pedro Miguel, a channel through the slides would have to be cut by hand labor and dynamite". Photo and narration from Ron Armstrong's book, The Panama Canal - The Invisible Wonder of the World. Above photo taken on September 13, 1913 shows the Cucaracha Slide on the right has filled in to the 65 ft. level, 25 ft. over the finished channel bottom. It later closed the channel completely. The Cucaracha Slide has been a real nuisance for the Canal Diggers since it started sliding in 1907 and has continuously filled in the channel as soon as it was cleaned out. " It had a total area 47 acres and extended up the east bank of the Canal for about 1900 ft. from the axis of the Canal. When it began its progress was disconcertingly rapid. Its base, foot , or "toe" - these anatomical terms in engineering are sometimes perplexing - moved across the canal bed at a rate of 14 ft. a day. All that stood in its path was buried, torn to pieces of carried along with the resistless glacier of mud. Not content with filling the Canal from side to the other, the dirt rose on the furthur side to a height of about 30 ft. Not only was the work of months obliterated, but work was laid out for years to come. Indeed in 1913 they were still digging at the Cucaracha Slide and the end was not in site. This slide was wholly a gravity slide, caused by a mass of earth slipping on the inclined surface of some smooth and slippery material like clay on which it rests." From Willis J. Abbot's book, Panama and the Canal - In Picture and Prose. With no more track, dirt trains or steam shovels how were they going to clean this slide out so the water could pass and fill the rest of the cut to Pedro Miguel. Once there was water, dredges could be floated to the slide and start digging. Below was the plan of attack. CUTTING THROUGH CUCARACHA SLIDE After the blowing up of Gamboa dike, the southern end of the

Canal, beyond Gold Hill, was separated from the waters of the lake by

the foot of Cucaracha slide. Beginning October 6, 1913 forces of the

Central Division had been engaged in digging a trench through the top of

this barrier to allow the passage of the water from the north side.

Successive downward movements of the slide, however, kept closing the

trench, and it was decided to blow a gap in the barrier in the hope that

the water would rush through it. A ton and a half of dynamite was placed

in the toe, just opposite Contractor's Hill and exploded at 4.15 p. m.,

October 10, 1913. The explosion threw a great mass of earth and rock

high into the air, and stones were hurled as far as 1,500 feet on either

side, but the clay of the slide slumped back into place and closed the

break before any considerable amount of water had passed through. Later

blasts produced similar results, and the effort to clear the barrier in

this manner was abandoned on Saturday, October 11. Trenching with pick

and shovel was resumed that morning, and water began to pass through to

the south side of the slide at 3:43in the afternoon. During Saturday

night, a movement of the slide closed the trench. It was opened again

by 11 a. m., Sunday, October 12. and has remained open since. A force of

200 men with shovels has been engaged in keeping the trench clear, and,

with the assistance of the flowing water, making it deeper and wider.

By 4 p. m., Sunday, pipe connections had been made with a water tank on

the south side of Contractor's Hill and the work of the men with shovels

was augmented by sluicing with a 3-inch hose along the lower side of the

barrier. During the forenoon of Monday, October 13, a 2-cylinder

air-driven pump

and connecting pipe and 4-inch hose were brought from Empire and

installed on the north side of the slide. At 2.50 p. m., this outfit

began supplying water at 150 pounds pressure for sluicing the

northern, or upper, part of the trench. This so facilitated the work

that by 4 p. m., the water was flowing over the slide at the rate of

about 40 cubic feet a second, in a stream from six to eight feet wide

and approximately a foot deep, moving about six feet a second.

It is believed that this method will so increase the flow as to

fill the south end of the Cut within a convenient period, though all

calculations may be upset by further movements of the slide. The

material of the slide is a dense, adhesive clay, intermixed with

stones up to two feet in diameter, and does not yield easily to the flow

of water. Canal Record Volume VII October

15, 1913

|

|

Above and just below, are two great photos of the blast that was mentioned in the article. Above is looking north and below south.

|

|

As explained in the Canal Record article, the blasting didn't work because of the thick clay mud, so it had to be dug by hand. The idea was to dig a gully and let the water eat it out and create a channel. This was a monumental task and didn't work at first. The photos below show the hand digging and then finally a channel is opened up for the water to flow.

|

|

|

|

Home|

Photo

of the Week | Photo

Archives | Main

Show Room | Photo

Room | Military

History

PC History

| Gift

Shop | Links