Balboa

lay below, a conduit for cars traveling from the locks and the little towns upcanal to

Panama City. I tried to imagine the setting in 1907, before Balboa was built, when the

landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of the creator of New York's Central

Park, and sculptor Daniel Chester French were sent down by the national Commission of Fine

Arts to suggest how the canal and its environs might be made more picturesque. "'The

Canal," they wrote in their subsequent report, "like the Pyramids or some

imposing object in natural scenery, is impressive from its scale and simplicity and

directness. One feels that anything done merely for the purpose of beautifying it would

not only fail to accomplish that purpose, but would be an impertinence."

Impertinent or not, Balboa had to be built nearby to

accommodate administrators and workers, and it required landscaping as well as houses,

offices, schools, and so on. Goethals wanted "a town that shall be a credit to the

nation and a place of comfort for those who inhabit it." He wanted, more precisely, a

150-acre town site to support 130 buildings, a layout of streets, walkways, sewers, and

water lines, and everything landscaped.

By this time, the Administration Building was already

rising on an artificial mound at the base of Ancon Hill; it would soon take shape as an

Italian Renaissance complex with a covered central entrance, dominating everything on the

plain below. It still does-including even McDonald's. But the young man who in 1913

finally took the job of laying out the town, William Lyman Phillips, was determined to

make the rest of Balboa appealing on a more human scale.

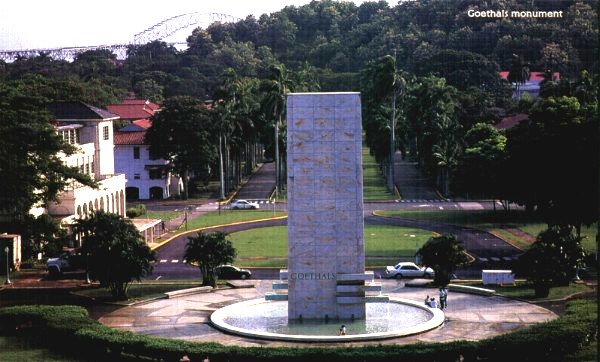

Exactly 108 steps below the Administration Building is the

garish fountain dedicated to Goethals, a monolith in white marble. More impressive are the

corutu trees on either side, 40 feet in circumference, with vast green canopies,

and the prado beyond, the formal approach to the administrative hill that Phillips,

who had been a student of Olmsted Jr.'s at Harvard, designed. Royal palms line the prado.

Phillips didn't care for these "feather-duster trees," but Goethals did, and

so they are seen everywhere in Balboa. The buildings shaded by them are uniform, with

raised porches and the ubiquitous red tile roofs.

Phillips accommodated the town to its natural setting, in

sharp contrast to the faux palace above it. His enlightened town plan, with winding

streets and bountiful landscaping, avoided of whenever possible the linear regimentation

dear to the military; rendering Balboa a more relaxed environment.

Goethals offered little support to the young, inspired

landscape architect; finally Phillips departed Panama in disgust, neither his plans nor

the effects of his ambitious landscaping fully realized. Another landscape architect, one

of several brought in to finish up Balboa, remarked of Phillips, "I don't know who he

was, but he was a master." Phillips also "may have been the only man on the

isthmus who understood the importance of making a visually harmonious tropical town which

would reflect the rhythm and style of life in Central America," according to his

biographer, Faith Reyher Jackson, writing in Pioneer of Tropical Landscape Architecture.

The Panamanian architect and historian Samuel Gutierrez told me that "gardens were

kept as an integral part of the houses, and the houses were so well suited to the

tropics." I found the community to be like a North American suburb, the winding

streets set about with small houses and large ones of a similar design, linked by the

profusion of plants and by a common, if vague, sense of purpose.

The open foyer of the old U.S. Post Office next to the

plaza, also designed by Phillips, suggested a precursor of the mini-mall. |

|

|

|